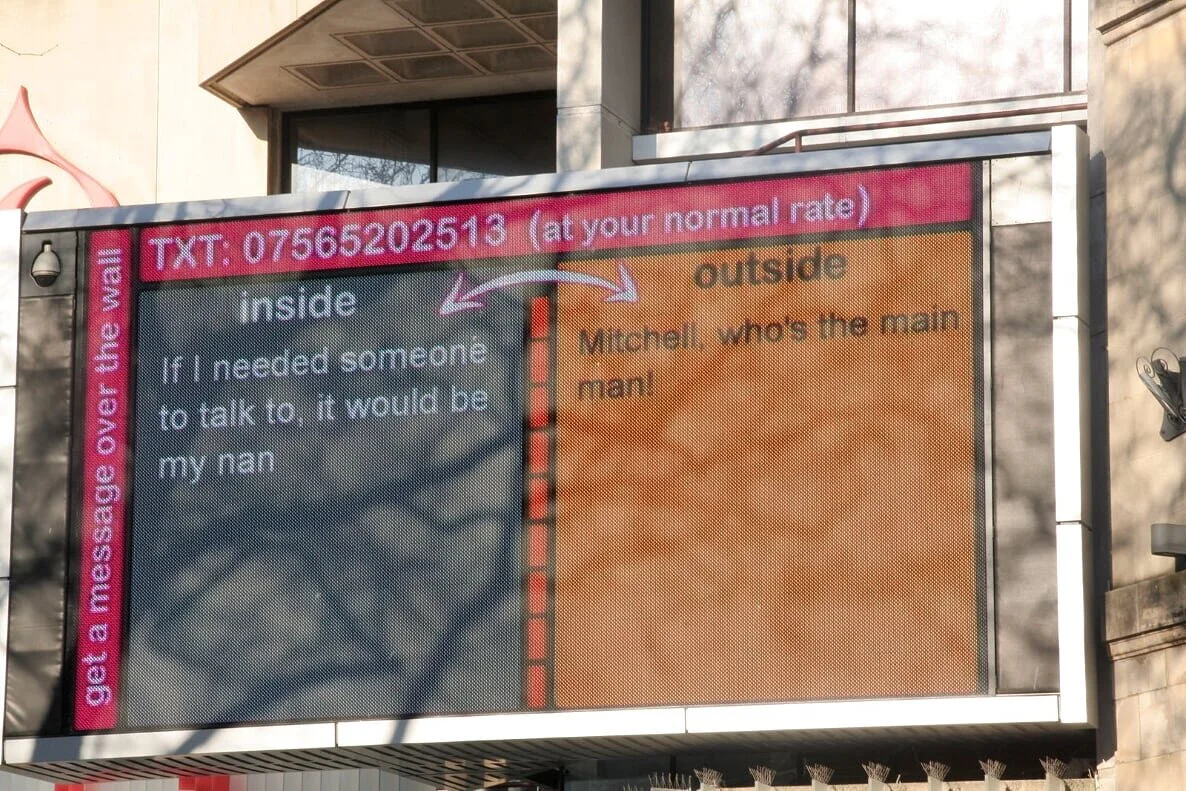

TXTInside/Outside, 2012

Cleared Statements by young people in custody for the BBC Big Screen in Cardiff.

The title of the project alludes to connecting the inside and outside of a prison via the medium of text messaging as part of a broader TXT2 project by Glenn Davidson and Anne Hayes.

The key idea for the piece was to collect, publish and ‘release’ the voices of young people held in custody (Inside), to be seen, heard and responded to by the public at large (Outside). The focal point of the action was a ‘stage event’ in the centre of Cardiff, where the text messages of a small group of young people in custody in South Wales were displayed on a large screen, with the public being invited to respond by texting their own messages. A documentary film from the event, which included the projections and interviews with the public, was subsequently shown to and discussed with participating young people in custody.

Continued..

The social worlds of most young people today are mediated through digital technology, mobile and online communication, including social networking sites. Without wishing to fetishize the ‘new media’, and especially its ‘sway’ over young people, it is probably fair to say that in the minds of many people, the mobile phone has become an emblematic tool for (young) people to connect with one another and to create dynamic, fluid, trans-local communities of engagement, and to socialize through shared verbal art and play. The mobile phone has also become a powerful symbol of social freedom, the freedom to communicate when and where one chooses (with the downside of being always contactable to the point of surveillance), to arrange, to rearrange, to disrupt, to identify.... Mobile communication technology is unavailable to young people in custody.

In today’s world, the denial of access to mobile phones is probably one of the most fundamental aspects of social differentiation and disparity between those inside a prison and those outside. On Saturday 11th February 2012, the large BBC screen in the Hayes area at Cardiff city centre was used to display the messages. Postcards announcing the event and inviting participation were handed out by the team in the morning. At 12 noon a 3 hour event began. The messages of the young people in custody were displayed on the left hand side of the screen, while the passing public sent live SMS text messages for instant display on the right hand side. Occasionally, additional prompts to the public were displayed at the bottom of the screen. A live roll of adjacent text messages from the young offenders and the public was created putting them in ‘dialogue’ with one another. Continued..

The Hayes Cardiff with BBC Screen

famous for one minute reveller publishes txt

TXT2 software running on BBC Big Screen.

BBC interview

crowd addressed through txt message

The Poncho Girls - all stars.

camera monitors from behind the screen

Wyn Mason and Dr Richard Owen conduct public interviews, people express their concerns for young people in in prison.

Boys in prison, some tears as they see public respond to their txts, expressing feelings about their lives inside.

Inside HMS Parc - young people to type their messages ready for the live TXT2 event.

The young people in custody who saw their messages displayed on the large, public screen in the film appeared to be profoundly moved. A sense of authorship, gaining a voice – even in a brief moment of public performance art – and the public’s responses to their own messages, demonstrated to these young people that they can make themselves heard and be taken seriously, however briefly. Their responses were strong, ranging from tenderness to hilarity. Experienced prison staff commented on unprecedented levels of attention and focus. Watching the film, which revolved around their own writing and its trajectory outside of the prison, these children perhaps felt socially validated or emotionally embraced.

Whatever the effects of the work may be, the process itself provided enough evidence that the project delivered its initial aim and promise to the young people in custody: they were able to bring out their own voices (necessarily controlled, censored, edited, anonymized), and to make a small mark in the world, to have others bear witness and respond. Self-worth and relationality achieved through uncontrolled social interaction and connectedness with diverse networks is denied to young people in custody on daily basis. However, the project has demonstrated that physical isolation of custody does not necessarily mean placing these young people beyond society’s reach, and vice versa.